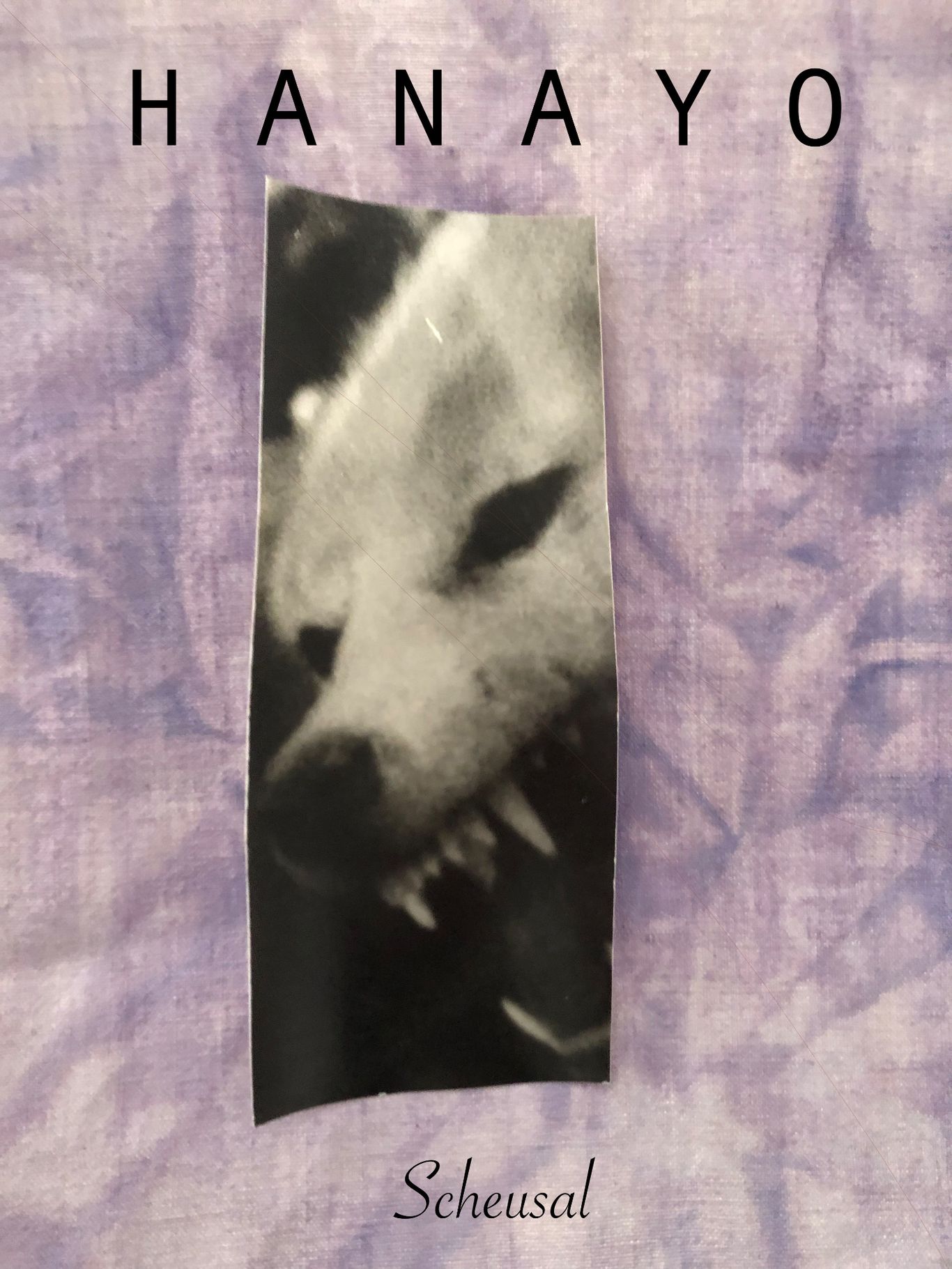

Hanayo

26.6.25. - 27.7.25

That Which Is Hard to See and Thus Comes Into View: Hanayo’s Photographs and the Eye of a Drifter

Midori Matsui

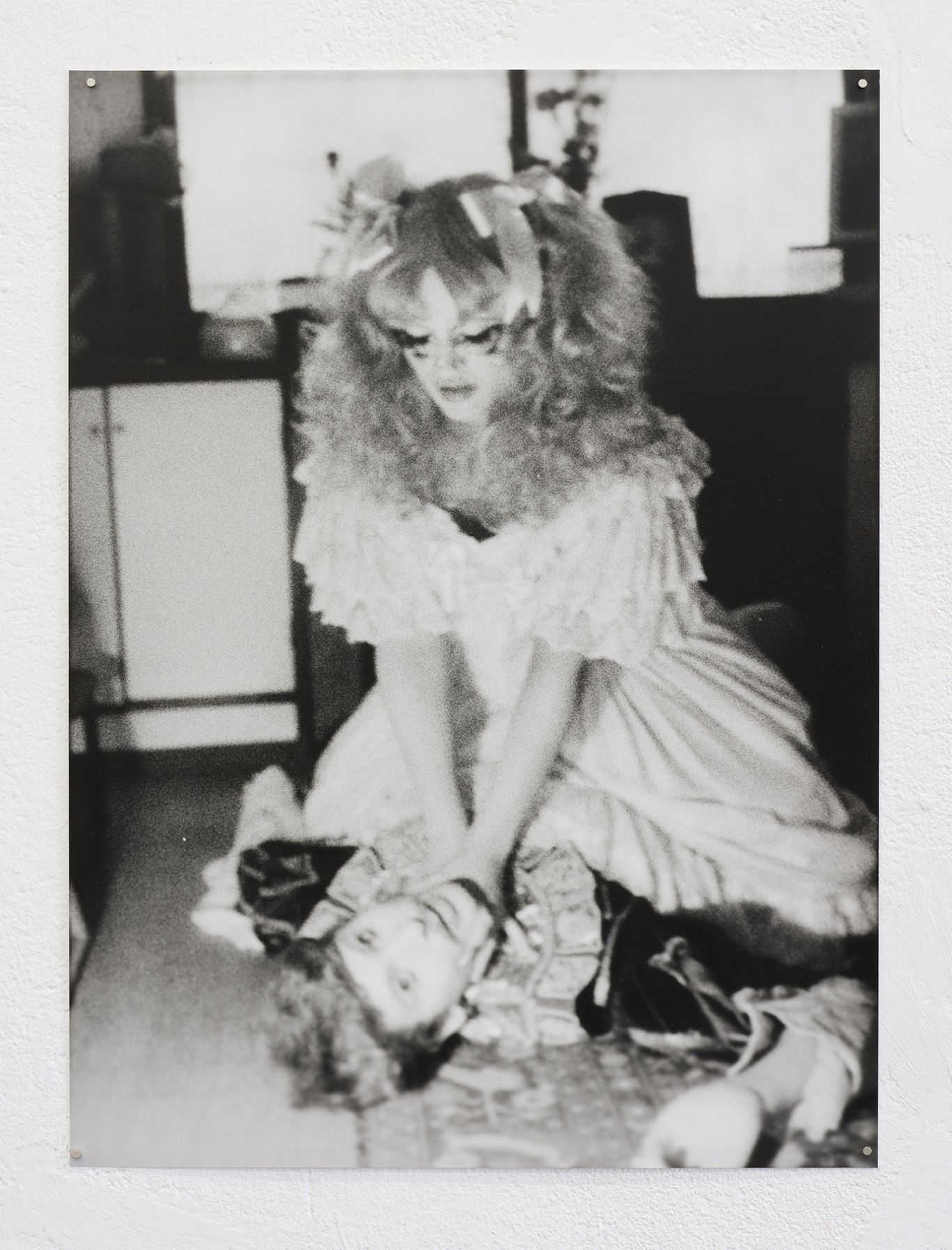

In the summer of 2021, a commemorative book on the path of Hanayo’s life as an artist, entitled Hanayo’s Underworld: Half a Century, was published. Its main contents consist of various materials that document Hanayo’s performances, as well as her photographs—both primarily from the 1990s to the present day. Each and every action she made was like a spark, keeping alive the flames ignited by practitioners such as those of Fluxus and the Situationist International in the 1960s–70s, who attempted to reduce the empty moments of life, which make it boring by conducting interventional actions to defamiliarize the everyday and constructing situations for people to gather.

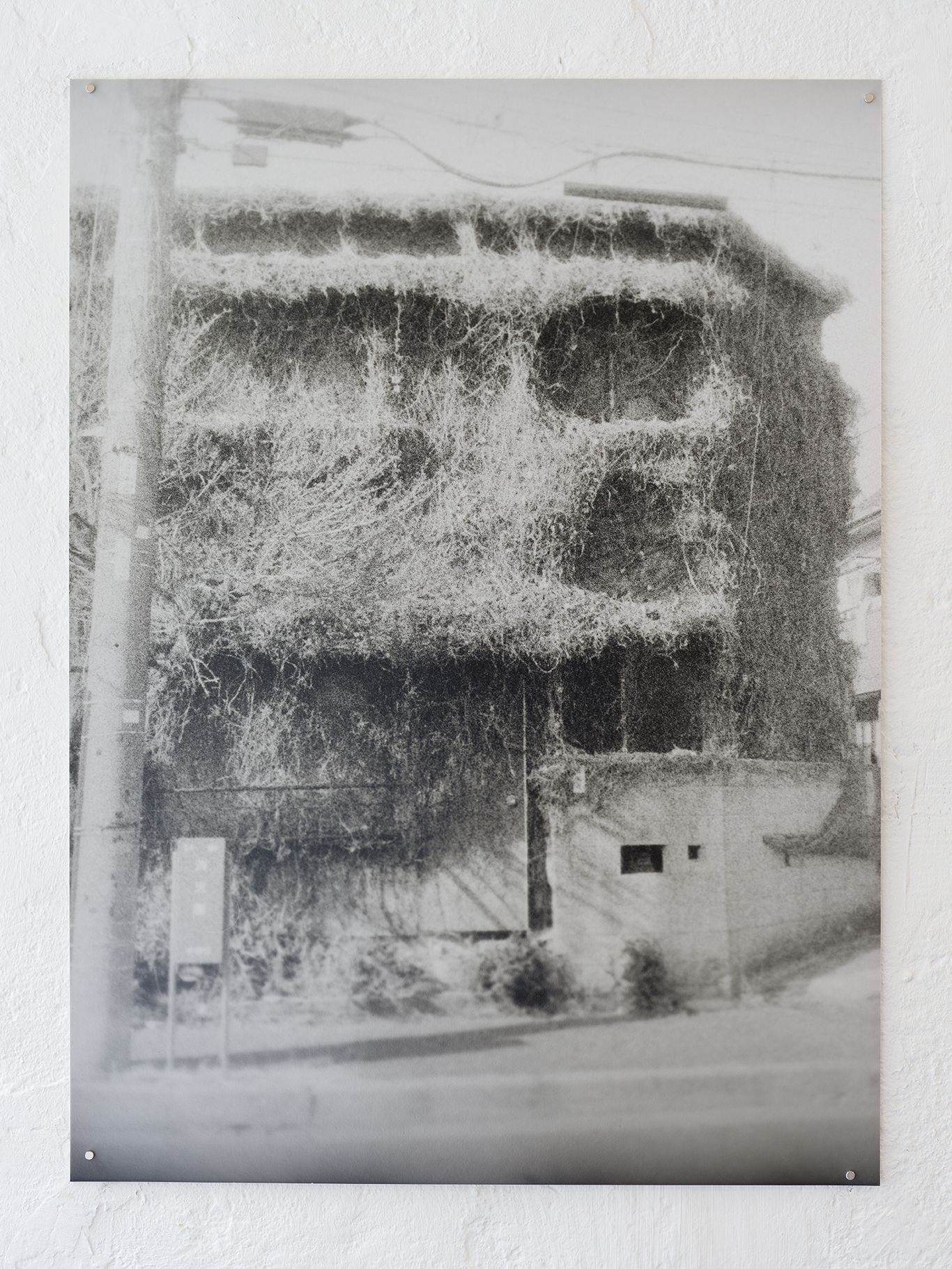

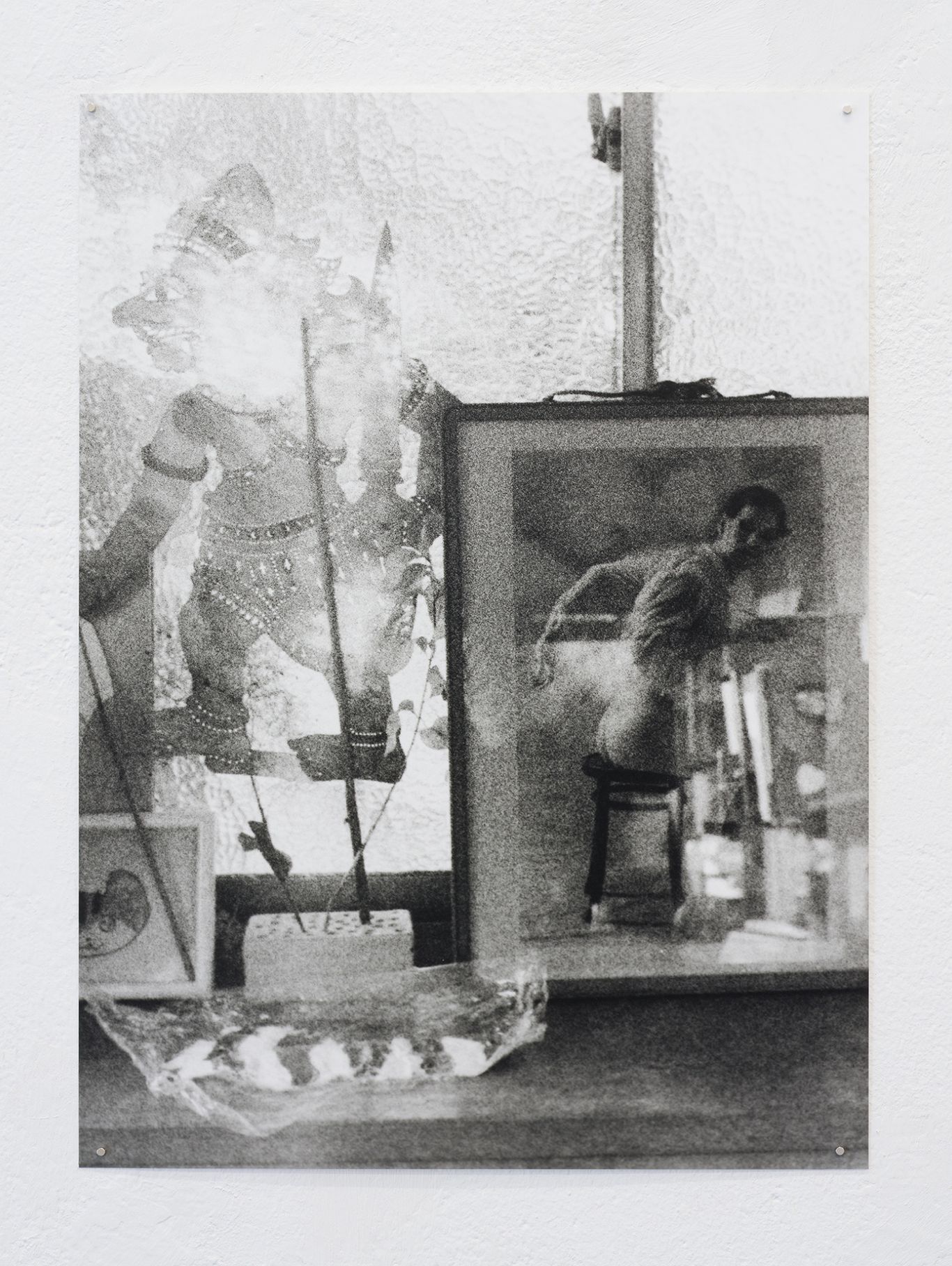

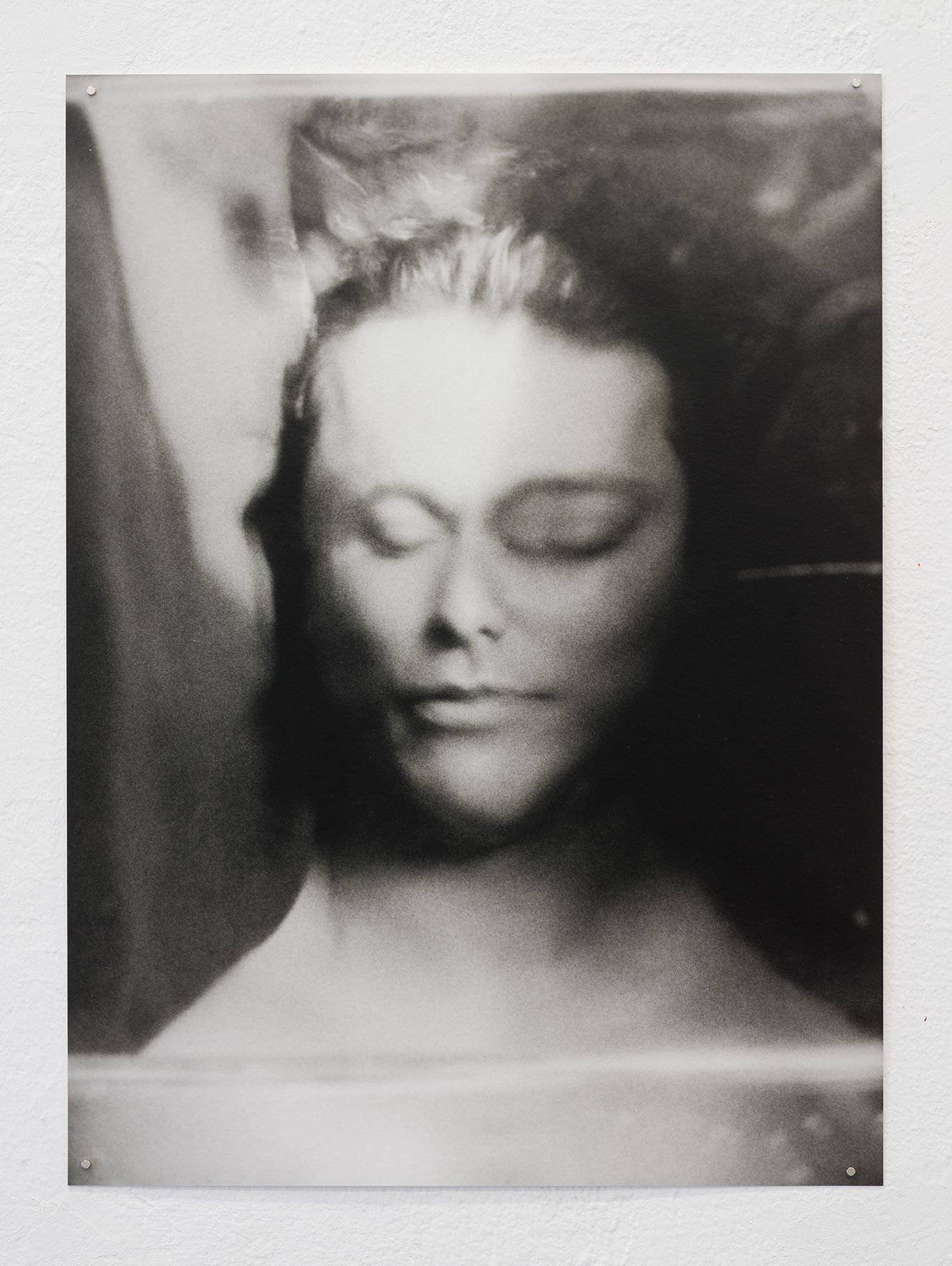

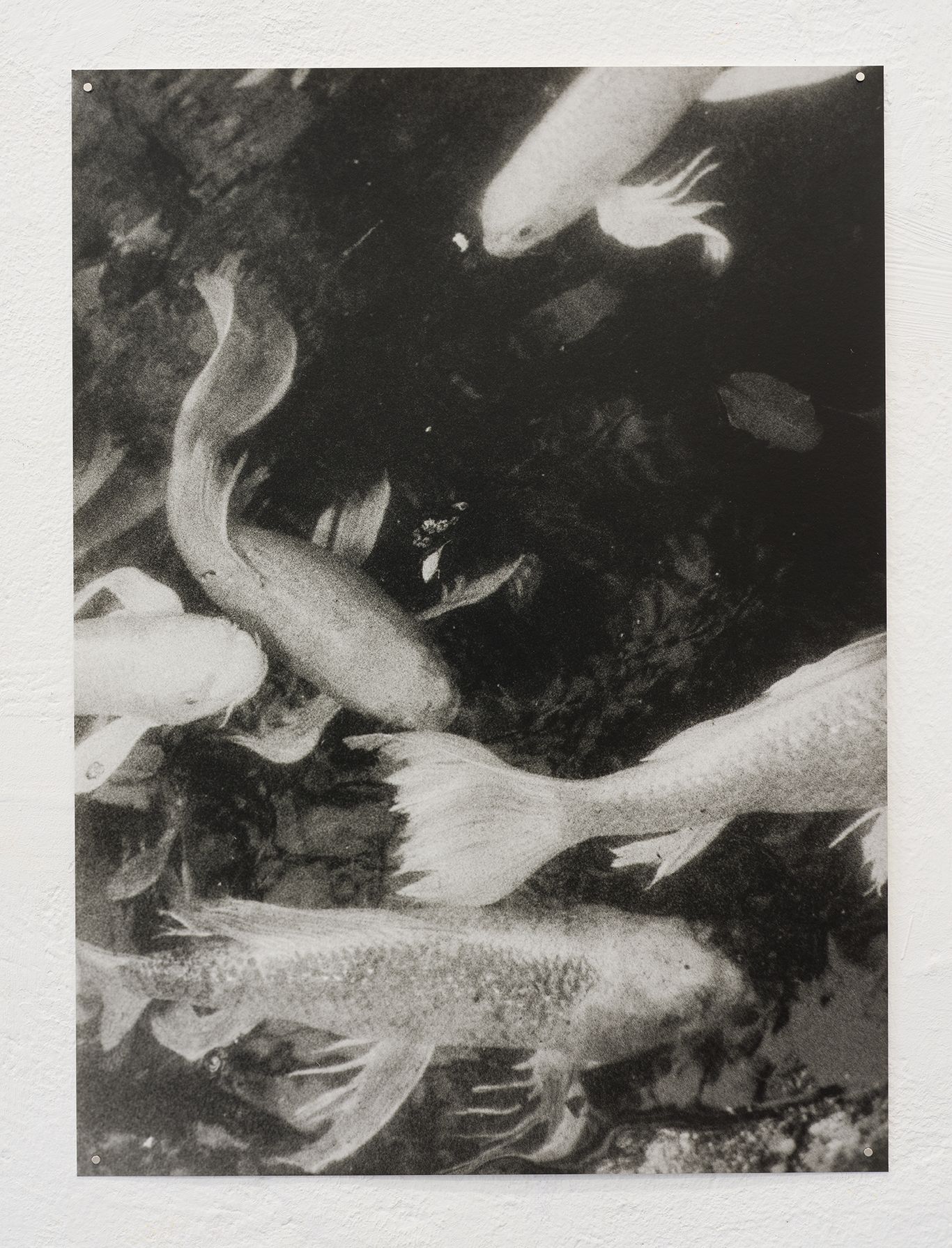

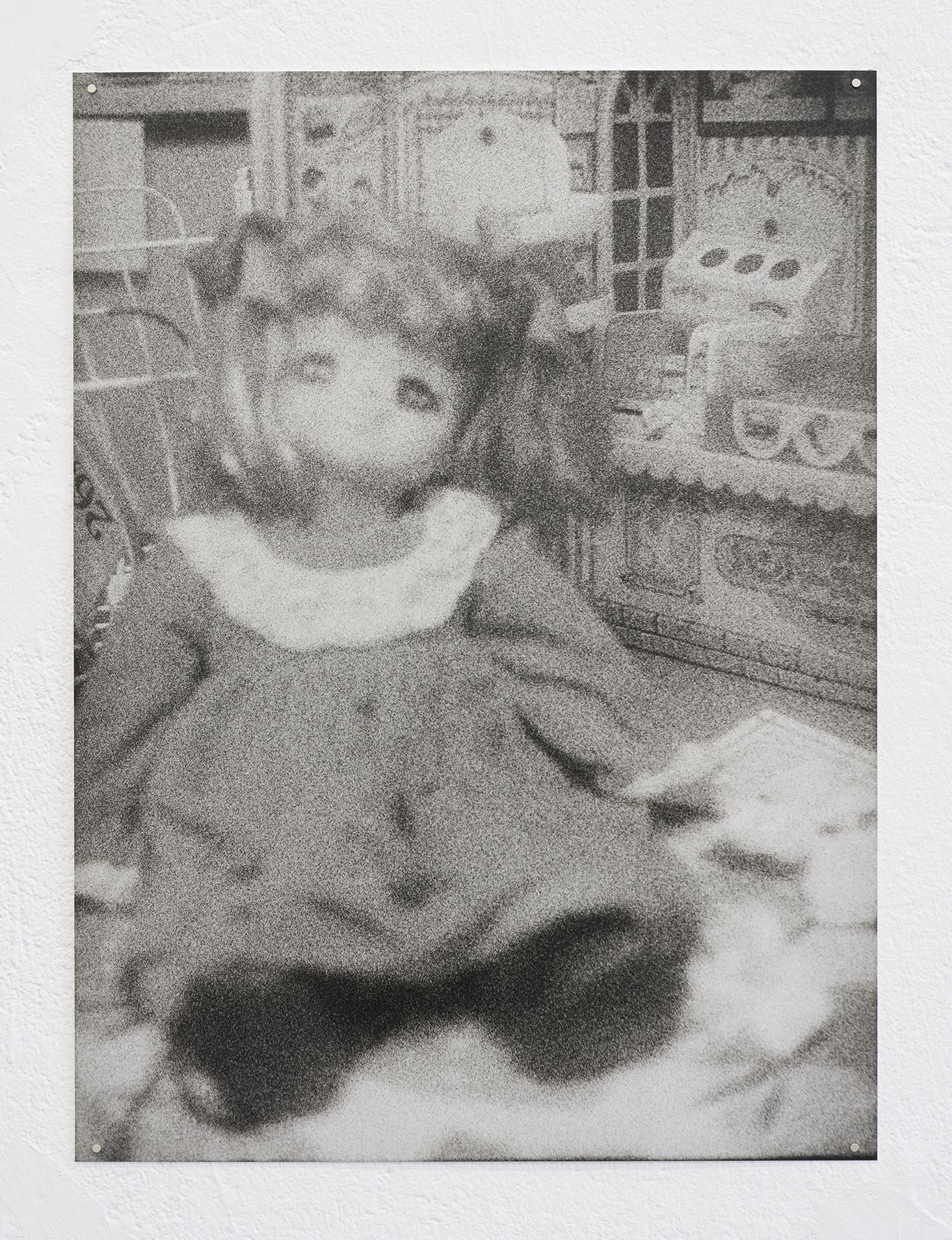

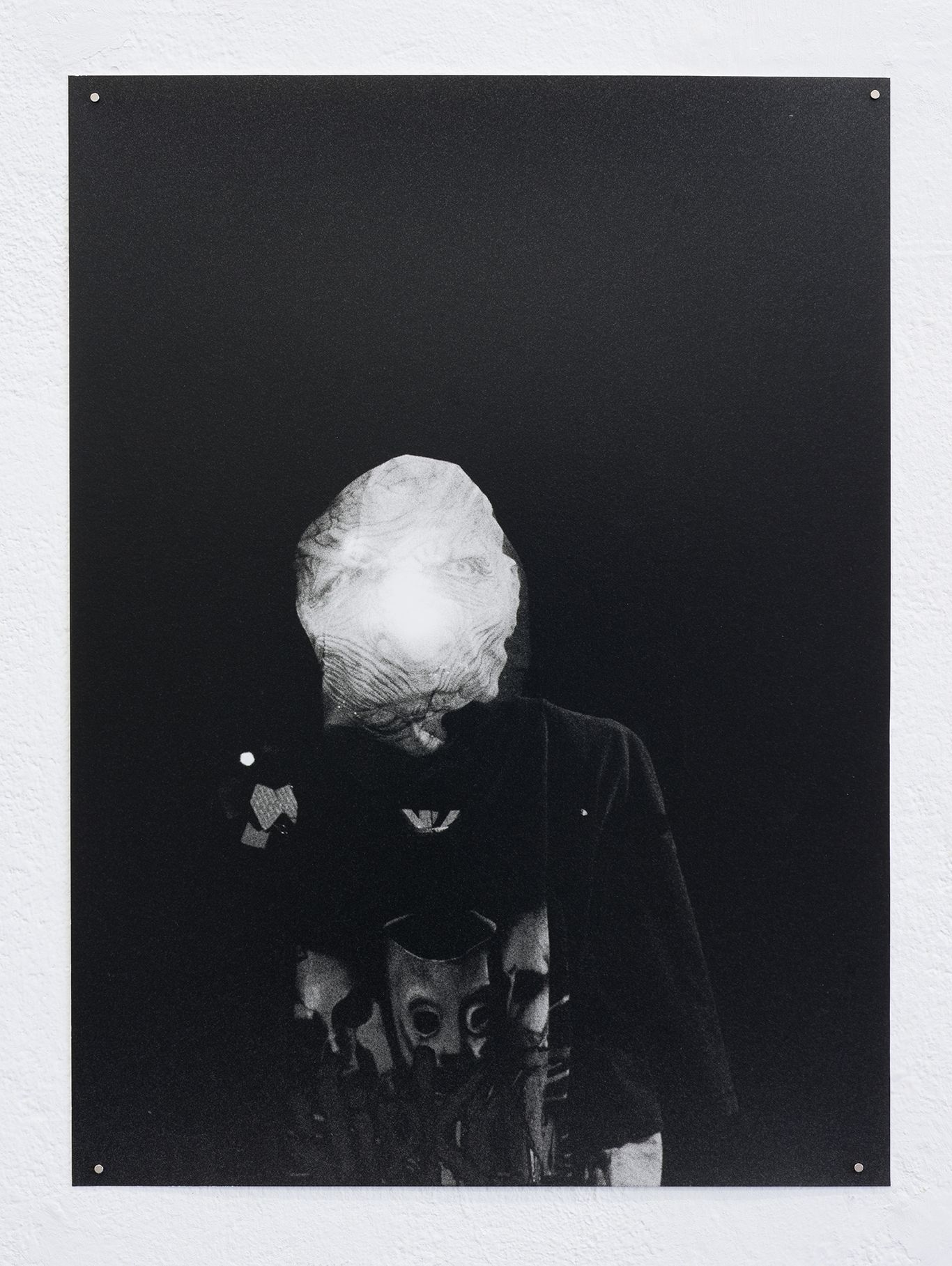

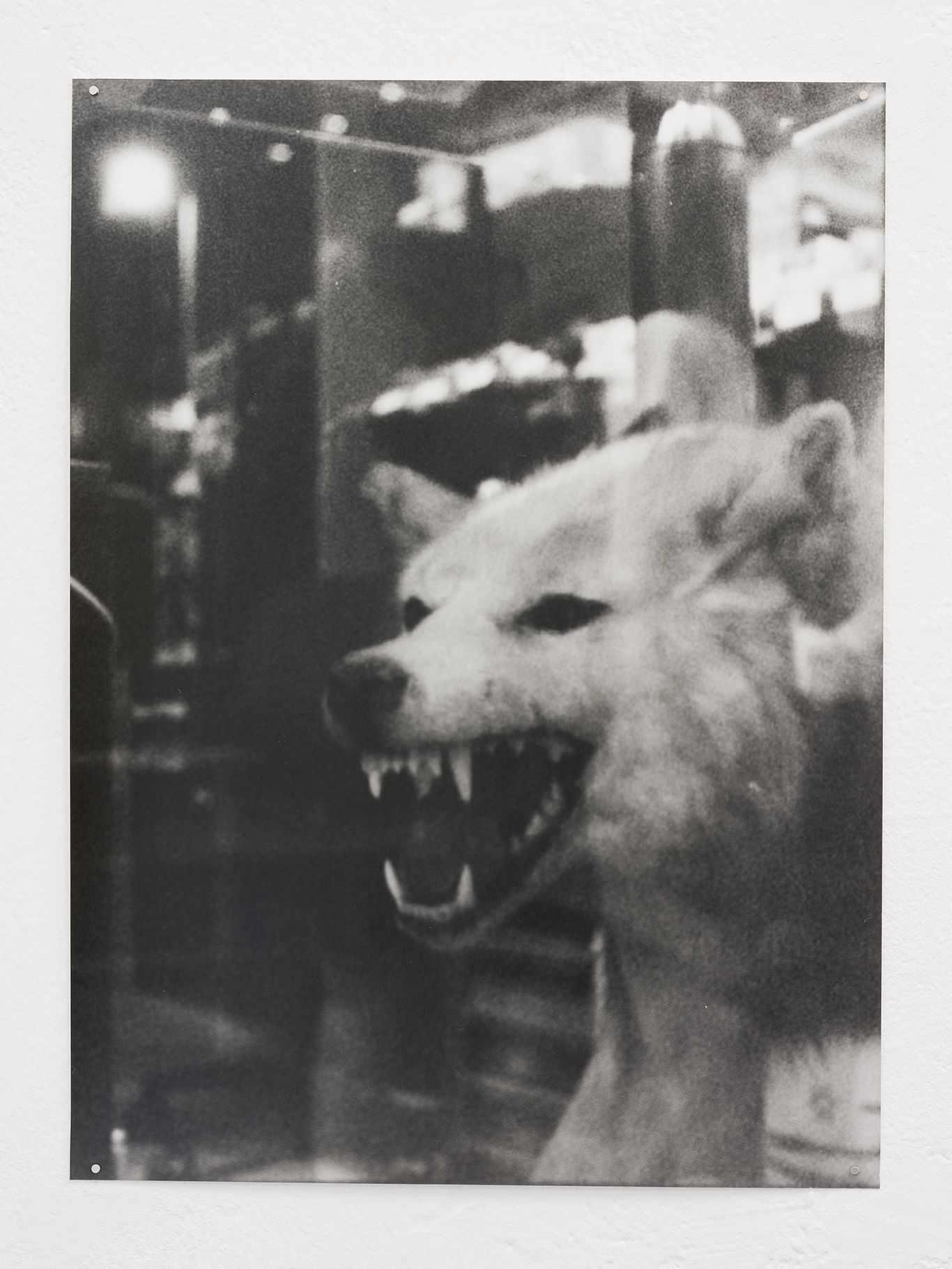

Hanayo’s art is essentially performative, as the documentation of her activity suggests. Taking photos and carrying out performances, for Hanayo, are one and the same thing, so it is pointless to consider them as two distinct practices. Some of the comments that people often make about her photographs, such as "It’s not obvious where and when this was taken" or "it’s not clear what is captured", prove that these photographs are taken through the eye of a drifter, while in transition from one place to another. From this mode of making photographs, it is also apparent that Hanayo treats all events, humans, animals, weather conditions, and so on, as things that constantly change form, floating between different phases, just like how any performance, while it is documentable through photography and video, is a fleeting phenomenon, with its true, transient essence not conveyable to those who did not share the same moment, in the same place.

This may seem irreconcilable with the conventional idea of photography that considers photographs to be that which record events or that which fix transforming modalities or flowing times as images. The way Hanayo takes photographs, however, does not contradict the fundamental fact that a photograph is a trace of light. In Hanayo’s photographs, ‘lights’are tinted and toned by her emotions, from which a peculiar sense of humidity and of temporal and psychological remoteness arises.

Indeed, we cannot say that the resulting vision is not ‘real’ for Hanayo.

Hanayo’s photographs of landscapes and animals remind me of the word kūge [literally ‘sky flowers’]. It is a Buddhist term that refers to flowers seemingly existent in the sky, or any delusion that misperceives something unsubstantial as being right there. It also indicates flowers in the air seen by people suffering from a certain eye disease (namely eigen [clouded eye]). Despite these dictionary implications, the Zen master Eihei Dōgen considers kūge not as a negative sign. In his book Shōbōgenzō [literally ‘Treasury of the True Dharma Eye’], he points out that truth that ordinary people with common sense tend to neglect, or new perceptions of life outside the scope of one’s awareness, are rather hidden in what just seem optical delusions or misperceptions.

Hanayo’s photographs have nothing to do with memories accumulated in a chronologically accurate order. Rather, it seems to me that they capture moments in which vague ideas people have about life and death emerge, out of mundane, trivial scenes seemingly unrelated to such issues, in the form of images that feel nothing but ‘essential’, or in other words, in which recognitions or premonitions that have been dormant deep in the subconscious manifest themselves, triggered by ever-so-slight cues, as absolute visions — which we can indeed call ‘sky flowers’, can’t we?—while Hanayo takes such photographs by instinct, without clear intentions to do so.

Dōgen states that you can spot a working of the eye where it is clouded, and when sky flowers bloom brilliantly, the essential natures of things become obvious. That said, we humans get our hearts moved when engaging with a phenomenon, and we heighten our perceptions by grasping the vision of its essential nature. We practice this act endlessly, as long as life continues. Hanayo’s photographic work will also continue, like an endless diary, as long as she continues to engage with the world.

(Excerpt from an essay of the same title written in 2021, translated by Yuki Okumura)

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Untitled, Gelatine Silver Print, 2025

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Photos: Nick Ash